REDWOOD VALLEY, 6/19/20 — Toxic cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue-green algae, is popping up in many areas of California. On June 12, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) sent out a press release advising people to be on the lookout for harmful freshwater algal blooms (HABS) as they spend time in and around bodies of water.

Within the last thirty days, cyanobacteria has been verified across the state, although the California Water Monitoring Council’s HAB incident map* shows cyanobacteria flourishing more near the coast and clustered near San Francisco, Clear Lake, Palm Springs, and around a few lakes and reservoirs.

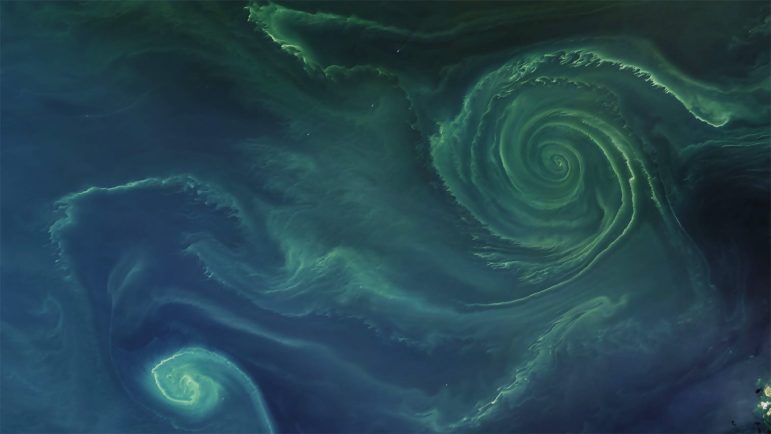

Seán Doran

As summer continues, the weather warms, and bodies of water start to evaporate at a higher rate, HABS are likely to increase in California’s waterways. Because HABS can be dangerous, and sometimes even fatal, scientists that study harmful algal blooms believe it is important to communicate with the public about what HABS look like, where they are, and how to avoid them.

Harmful algal blooms have a variety of looks. They may take on the appearance of foam, scum, algal mats, or large chips of paint. Sometimes they hide out of sight and are not visible at the surface at all. HABS can also exude strong odors similar to the smell of rotting plants.

HABS may or may not produce toxins — and it’s not possible to discern whether or not they are poisonous or not based on their appearance.

Harmful algal blooms are dangerous to humans, animals, and the environment. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HABS can poison humans and animals that swim in the water, drink the water, or are near the water. Although it is rare, the toxins from HABS can be fatal. HABS can also make a person or animal sick from eating fish or shellfish that have been contaminated with harmful toxins. Harmful algae blooms with cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins may end up in drinking water, posing a serious health risk. There is no regulation that dictates the amount of cyanotoxins allowed in drinking water. However, there is a non-binding advisory for two cyanotoxins from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that suggests what amount is safe in drinking water.

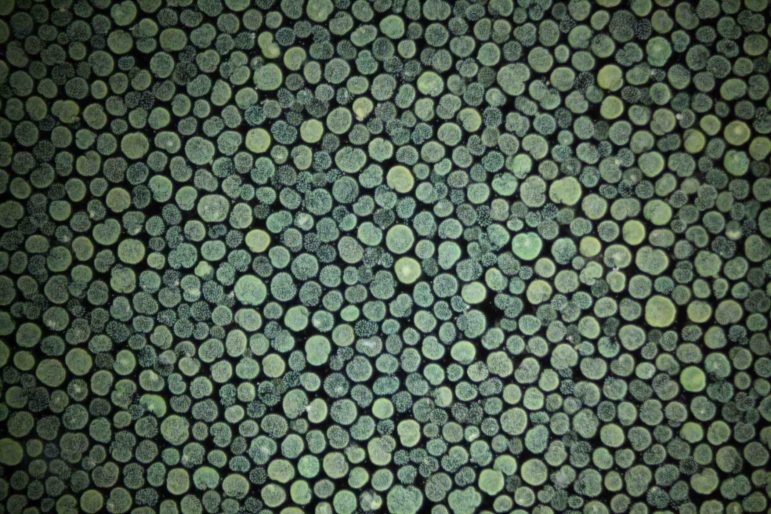

Both cyanobacteria and algae, which cause HABS, are ancient life forms. The oldest known fossils of cyanobacteria come from 3.5 billion years ago, and algae dates back one billion years. These photosynthetic organisms are crucial to aquatic ecosystems, serving as the base of marine food chains. However, when their growth is accelerated out of control due to a variety of conditions, they grow rapidly into blooms. This causes the dangerous toxins present in fresh and saltwater ecosystems around California and the world.

“When conditions are optimal, including light and temperature, elevated nutrient levels, and lack of water turbulence, cyanobacteria and some algae can quickly multiply into a harmful algal bloom (HAB),” wrote the California Water Quality Monitoring Board in their April 2017 HABS Report. “These conditions have been heightened by drought and climate change.”

With the right circumstances in place, HABS may become dense enough to stop sunlight from reaching far into the depths of the water, altering the ecosystem, and may cause oxygen depletion as they decompose, taking away necessary oxygen from fish and plants.

The conditions that make cyanobacteria and algae ripe to turn into HABS have been increasingly present in recent years.

“The increase in cyanobacteria is a direct function of climate change,” said Scott Greacan, Conservation Director at Friends of the Eel River. Because HABS thrive in high water temperatures and low water quality, their environment is being expanded by drought, which is caused by climate change, as well as diversion and pollution, Greacan explained.

“Toxic algae love deep, still, and warm water,” said Susan Fricke, who works on the Klamath. “If you give it something like a reservoir, you’re basically turning a river into a big, warm, nutrient-rich bathtub. The water moves slower, gets warmer, and evaporates faster, all which leads to more toxic algae,” explained Fricke, the water quality program manager for the Karuk Watersheds branch in northern Yreka County.

HABS also form in moving water when there are low flows and the water is relatively warm.

Fricke believes that due to drought conditions across the state, HABS are likely to appear in California’s rivers and streams earlier than usual.

HABS are not unique to California.

“Cyanobacteria is a huge water quality problem across North America and from what I’ve seen across the world,” said Scott Greacan, Conservation Director at Friends of the Eel River.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), HABS occur in all U.S. waters. In October, the 19th International Conference on Harmful Algae will take place.

A HAB event can last anywhere from a few weeks to longer than a year. Currently, there is no method in place to control or stop HABS.

Keith Bouma-Gregson, who works for the State Water Quality Control Board, suggested that in order to keep safe from HABS, people should keep healthy water habits this summer by paying attention to the Water Quality Monitoring Council’s posted advisories and be mindful of water conditions.

“Avoid contacting algal scums and algal materials and swallowing untreated water,” he said. “When in doubt, stay out.”

—

A few notes and resources about HABS

- Although the CDFW press release cited in this article only references fresh water HABS, HABS also live in marine and brackish environments. You can find more information on saltwater HABS at California HABMAP.

- If you think there are unreported HABS in a water system, you can report it here and the Water Quality Control Board will look into it.

- You can follow this link to NOAA’s harmful algal blooms page to find more information on HABS around the country.

- Here is the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website on HABS and associated illnesses.

- If you would like to know what HABS look like, you can go to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservations HABS photo gallery.

—

*This map shows where cyanobacteria is, but does not show where it isn’t. Because there is no mandatory state or federal regulation of cyanobacteria, monitoring is not consistent around the state and is done on a voluntary basis. This means that if the HAB map shows a certain body of water as being incident-free, that does not mean there is no cyanobacteria.

Toxic Blue Green Algae can kill your pets. Dogs who drink, swim, or play in ponds, streams, or rivers polluted with Toxic Blue Green Algae can die. If they have been in or near affected water, even licking their fur or feet can cause illness or death, and horses and other livestock that drink infected water can become deathly ill. Toxic Blue Green Algae poisoning usually cannot be cured, however, test kits made specifically to test water that might harbor Toxic Blue Green Algae are available on Amazon under Blue Green Test: 5Strands/Blue Green Algae Test.