UPDATED 9 p.m. — Large portions of Potter Valley has lost power, and PG&E is not indicating that this is part of the planned power outage, and so it remains unclear as to whether this is part of the planned power shut-offs or the result of the high speed winds in the valley. As of the time of publication, PG&E has not listed anything about this outage on their outage map, meaning we are not aware if it is a planned outage or simply the result of the wind. However, no fires have been reported.

WILLITS, 10/25/20 — Californians have learned many hard lessons in the last four years, since the effects of climate change began to be seen acutely in ever worsening wildfires. Perhaps most importantly we’ve learned to take threats and warnings about fire weather seriously.

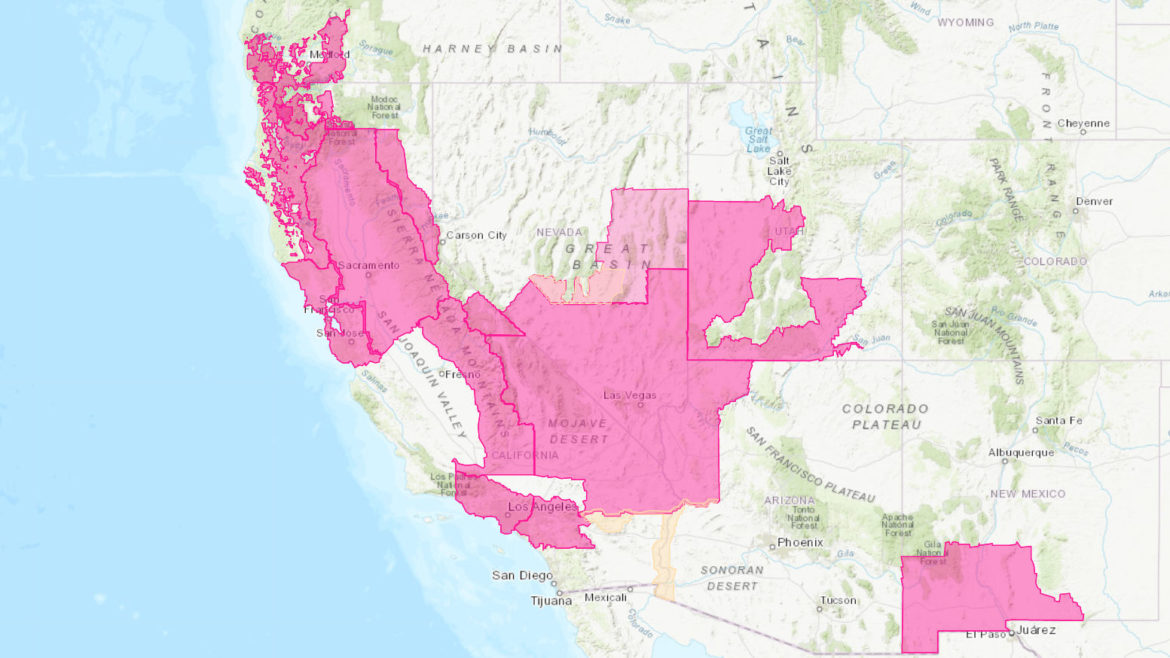

(Click here for the full size version of the red flag map)

But with this new readiness comes an awareness that conditions and forecasts shift rapidly. Though huge swaths of the state remain under a red flag warning, and with dangerously fast dry winds expected to kick up this afternoon, forecasts have shifted east, and Pacific Gas & Electric has dramatically scaled back their plans for shut offs in Mendocino County. Now only 1000 customers are slated to have their power turned off.

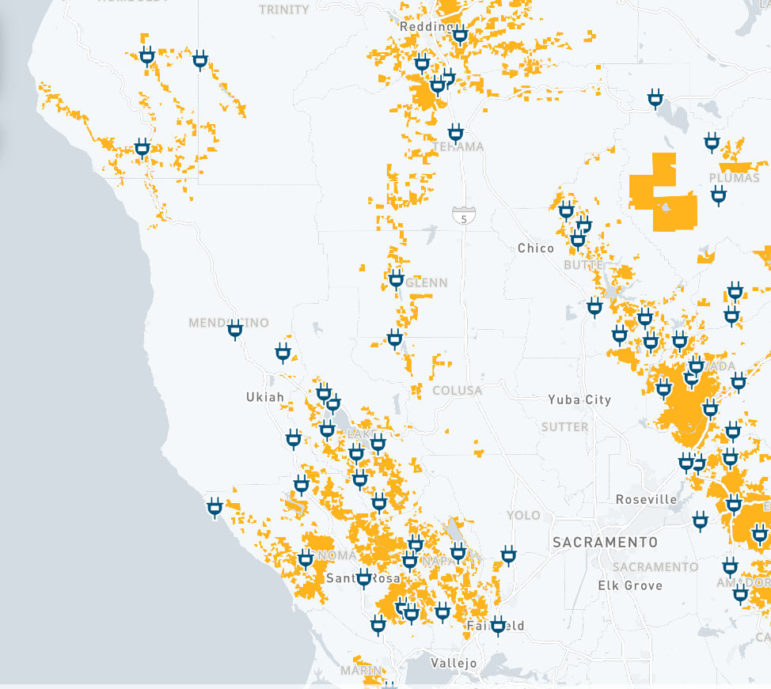

You can find information about charging stations located in Potter Valley and Hopland at PG&E’s website here.

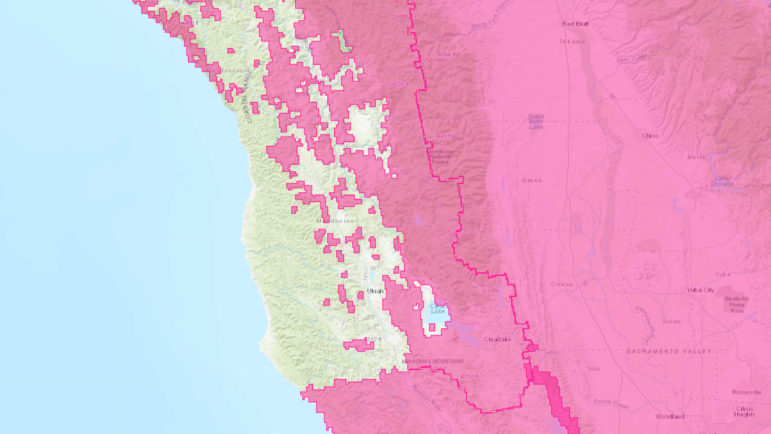

The City of Willits announced earlier this morning that they had recieved word from the private utility company that the power would not be cut to Willits. The City of Ukiah, which operates its own power utility and distribution lines, is likewise not slated to have their power cut. PG&E’s current forecast outage map show only small areas along the Lake County line, or along high wind corridors like SR-20 above Lake Mendocino — also included are the far northern portions of Mendocino that are connected to the power gird through Humboldt.

However, very large areas of Sonoma, Napa, and Lake counties will lose power, along with chunks of Humboldt. (Check here for the full size outage map)

What exactly is going on?

Now that we’ve gotten the basics of the immediate situation explained, it’s worth stepping back and taking a look into just what’s going on with the weather and power infrastructure in California.

Currently an air mass sitting over the Great Basin is beginning to push its was southeast through California towards the sea. This air mass is extremely dry, earlier today a humidity reading 3% was recorded in Siskiyou County — that’s nosebleed dry. As this air pushes southwest gusts as high as 70 mph, or event near 100 in portions of the Sierra Nevada are expected.

This extremely fast dry air is meeting conditions on the ground, literally, where vegetation and even the soil have reached record levels of dryness for this time of year. The drought conditions that began this previous winter (with effectively not notable precipitation for the month of February) are continuing to worsen as the state remains hotter and drier than normal for this time of year. These conditions mean that a tiny spark can becoming a raging fire in no time.

As climate scientists Daniel Swain, one of the foremost experts on how climate change is exacerbating fire weather, said on his blog WeatherWest.com, “In fact, this wind event is poised to become the strongest of the season so far (by a wide margin) and will likely approach the magnitude of the extreme autumn wind events in 2019 and 2017.”

Now the question of power: as most of us known, a tremendous number of the deadly fires of the past few years were started by failures of PG&E equipment. Most of the fires in the 2017 Fire Siege were sparked by PG&E power lines or other equipment, the Camp Fire was started by the failure of a PG&E electrical line which was supported by a 100 year piece of cast iron. Even the Kincade Fire of last year, which forced the evacuation of 200,000 people from Sonoma County, was started by the failure of a PG&E transmission line near the Geysers.

These fires together have killed more than 120 people, and causes several billion dollars in damage. Suits and political pressure resulted in the bankruptcy of the company, and restructuring — but that’s “a whole ‘nother story.”

Needless to say, with this dubious record the utility company has made the decision to try to avoid future liabilities by sparking fewer fires. The task of upgrading century old equipment, clearing trees, and burying line, will be extremely expensive and is projected to take years if not decades. In the mean time the company has landed on the expedient of turning off the power to affected areas.

However, just where they turn off the power is not entirely straight forward. To understand why, a basic familiarity with the power grid is useful. PG&E opperates three distinct sets of infrastructure: power plants, power transmission lines, and power distribution lines. Power plants create the electricity, which PG&E then sends to its own customers, or sells to other utilities, like Ukiah, which buys much power from PG&E. However, other power generators, like Sonoma Clean Power, also send power they’ve created along PG&E lines.

That energy is sent via high powered transmission lines, which can range from as high as more than 500 kilovolts for the enormous Central Valley towers, down to 115kV for the lines that run along SR-20 from the Central Valley to Mendocino, or even down to 60kV for the lines that run from Redwood Valley up to Willits and then over to Fort Bragg.

These transmission lines can be though of as the freeways of electricity, and are built commensurately stronger. Such lines are generally strong enough to withstand even strong winds, and are usually tall enough to keep the lines free from nearby trees. However, in some places such as between Redwood Valley and Willits, these lower voltage transmission lines can be somewhat more flimsy than would be ideal.

Finally the power reaches* substations where transformers once more reduce the voltage before sending the power out along distribution lines, which can be thought of as the side streets of the system. These lines are the ones that eventually reach homes, businesses, schools, etc. and are a much power voltage — but they’re also not built to the same high standards as the transmission lines.

So when fire weather arrives, power utilities (companies in Southern California and even Oregon now do similar things) have to decide what to turn off. If the winds are high enough in some places they may need to shut off transmission lines, which has the effect of killing the lights to everyone down stream of that location. That is why it can be the case that people in areas unaffected by wind may sometimes lose power, because the transmission line dozens of miles away is being affected by that wind. Indeed, just such a thing occurred in Mendocino County last year.

But in the past two years PG&E says that they have done a great deal of work to strengthen transmission lines and build in bypass circuits to their system, allowing them to turn off power in a more targeted way.

For instance, the Hopland area used to be on a single circuit. The fart southeast corner of that circuit included homes on high ridges that are often affected by the worst of the fire weather. But in order to turn off those distribution lines, in previous years, it was necessary to turn off the entire circuit, leaving even downtown Hopland powerless, though the winds were low.

Supposedly much of this issue has been resolved this year, with far more “off-switches” built into the system, allowing for more targeted shut-offs.

This is the hope, and it’s likewise the hope that with these advances, and the ever sharpening weather prediction systems, California will be able to avoid the kinds of catastrophic late night fires that killed so many in recent years.

The next 24 hours will show us if the preparations were sufficient.

Here is out coverage of the issue from yesterday:

Here’s a map showing broader area showing how Southern California will also be affected.

Regions of critical fire weather.

A close up view.

Some more details on the winds.

And what things will look like in the south.

*Note: For you electricity buffs out there, we understand that alternating current and the flow of electricity generally mean that individual electrons are not traveling any notable distance down these lines, but for the sake of simplicity we talk about the power moving.