REDWOOD VALLEY, 6/19/20 — Last month was record breaking in California with daily high records temperatures set across the state.

On Memorial Day, Tuesday, May 25, South Lake Tahoe Airport reached 80 degrees, breaking its 1989 record of 79 degrees. Downtown Sacramento tied its record, of 100 degrees, reaching triple digits on May 25 for the first time since 1951. The next day, Stockton recorded 105 degrees, breaking the old record of 101 degrees in 1974. The heat stuck around downtown Sacramento, which hit 103, breaking a 102 degree record, also in 1974.

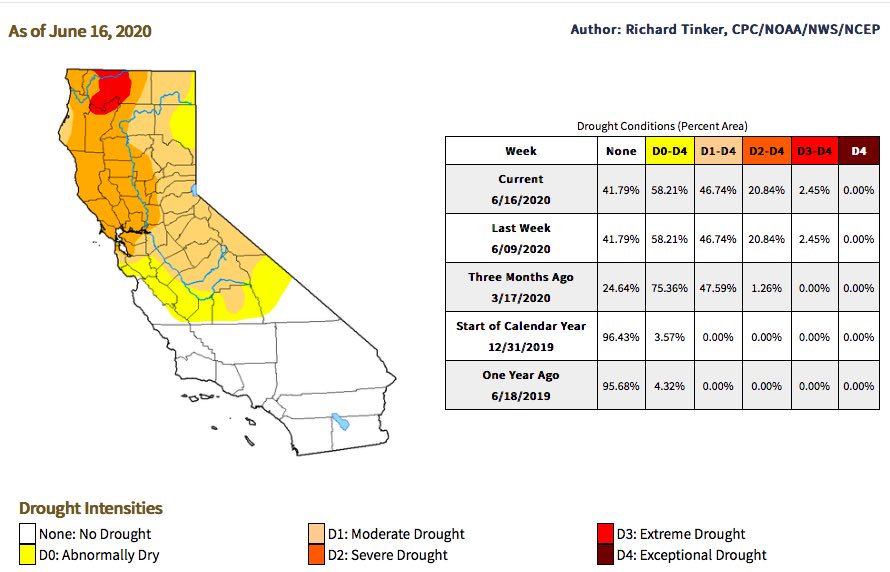

This May tied with May of 2016 for the warmest month on record for the planet. The northern hemisphere had its second warmest spring in history. As of May, 47% of California was experiencing drought conditions. In Mendocino County, “severe drought conditions,” defined by the U.S. Drought Monitor, prevail.

Climate Scientist Daniel Swain believes that as the world continues to heat up due to global warming, people are getting used to new, warmer weather and unusual climatic patterns. But, the differences in climate and weather seen and experienced day to day continue to be significant, explained Swain, who works at the Institute of Environmental Sustainability at University of California, Los Angeles. For the fire season, notable differences between this year and last year are already visible. Thousands of more acres have burned across California than at the same time in 2019 and Cal Fire predicts that there will be above normal wildfire potential through the summer.

According to Swain, the past six months have seen unparalleled low precipitation, exceptionally high precipitation, and record-breaking heat. And the scientist worries that as global warming continues to swiftly warming the planet, another parched February, extended and severe fire season, or uncharacteristically scorching Memorial Day weekend may start to seem average.

“We’ve seen so many temp records broken it seems mundane,” he said. “The fact that the May heatwave wasn’t record shattering makes it almost not newsworthy.” But, “If you take a step back and look at the historical record and ask — how unusual was this?” The answer is “more unusual than our perception would suggest because we’ve already gotten used to that baseline warming,” said Swain.

“In Mendocino and on the North Coast in general we’re not seeing the warmest period on record, but in the top five or 10. That’s a remarkable statistic considering we have information that goes back 150 years,” he continued.

Although NorCal saw a wetter May than usual, much of the significant precipitation skirted Mendocino. And where unusual rain did fall — such as in Eureka, which received 4.73 inches this May — it did not make up for the remarkable precipitation shortfall across NorCal.

California had its driest February ever, found the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in their U.S. Climate Assessment for the parched month. Only an average of 0.20 inches of precipitation fell in the state over the course of the month. The previous record, set in 1964, was 0.31 inches. Some places reported less than 5% of average rainfall and San Jose, Oakland, Sacramento and San Francisco, did not record one drop of rain for the month. As February came to a close, the Sierra Nevada snowpack, which is the source of one-third of California’s water supply, was only at 46% of its historical average, they wrote.

Now, some areas in Northern California have precipitation deficits greater than 25 inches — 25 inches less than the average — reported NOAA in their May 2020 National Climate Report.

Drought conditions are expected to continue through the summer and NOAA anticipates above normal temperatures for the coming months. The record breaking heat wave this May did not help the situation.

“What is unusual about this spring in coastal California is that we had an early season and fairly prolonged heat waves,” said Swain, who also authors a blog about California climate — Weather West. “It’s very unusual that they reached the coast,” he said.

He went on to explain that this year’s early warmth has just as much to do with the water as it does the air. Usually, a strong onshore wind blows in from the cool Pacific, keeping the immediate coast chilly, which meteorologists call marine influence. This results in the beloved “May Gray” or “June Gloom.” This year, that didn’t hold true due to persistent and more frequent heat waves that came from high pressure systems, which warmed the water, which in turn decreased the marine influence, creating a positive feedback loop.

The heat waves experienced on the coast in May were more reminiscent of the typical fall heat waves that occur once the fog has dissipated than of early summer heat, explained Swain.

It likely does not come as a shock that due to the hot and dry weather, Cal Fire’s Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook maps (available below) show an above normal potential for wildfire in Mendocino for June through August and much of Northern California for the same months. Already, the Quail Fire burned almost 2,000 acres in Solano county late last week.

In the state, 13,607 acres had burned as of June 14th. Last year at this time, only 10,552 acres had burned. However, we’re still below the average of 14,780 acres burned by mid June. What’s different about this year is that 2,405 fires have already been counted, higher than the average of 1,848.

“The key is not how much rain we get, it’s when it comes,” said Lucas Spelman, Cal Fire battalion chief and southern region Communications Officer. Spelman explained that the last three weeks to a month of precipitation that fell on California was the perfect time to grow grass. The grass that sprouted up in May is now drying up, becoming part of the fuel load and contributing to the large number of small fires.

Although more fires than usual are popping up, Cal Fire is able to fight them effectively and keep the number of acres burned low with the help of extra firefighters, who they brought on early in the season, said Spelman.

In terms of wildfire, “Last year was a bit of a reprieve,” said Swain. “2019 was a better fire year. I don’t think we’ll be as lucky as we were last year. I’m hoping we won’t see a repeat of 2015 through 2018. It’s hard to say, the odds are favoring a worse than average fire season.”

California is not the only place where there’s a likelihood of a big fire season. Globally, the past five years have been the warmest on record. The world is hotter and drier.

“Hot and dry. These are the watchwords for large fires,” said National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Ellen Gray in NASA’s 2019 report on the relationship between climate change and fire.

For Spelman, the hot and dry weather brings more work to do. He explained that the amount of drought, timing of precipitation, and a variety of other factors have created an exceptionally flammable environment. “Grab dead and live fuel and put them together with a growing California population that spends time recreating and doing all the things they do and you create the perfect storm,” he said.

California has always been fire prone in the summer — but now, it’s ready to burn during all four seasons, Spelman explained, citing the Thomas Fire in winter 2017-2018 and the Woolsey in 2018.

“We used to have fire season,” he said. “Now it’s fire season year round.”

As the earth has warmed, its likelihood of burning has grown.

“It’s easy, maybe too easy to become acquainted with temperatures as they warm,” said Swain. “We really notice them during heat waves but it’s warming the rest of the time too. Warming at night, warming in winter, warming even when it’s not particularly warm outside.”

Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook Maps (June – August)

Imagine if we put the mountain of money blown on COVID-19(84) into mitigating this REAL crisis of drought? 10% of the actual expenditures and the massive losses of economic output could have virtually eliminated the threat.

Priorities, priorities…